9 Research-Based Methods to Teach Toileting to People on the Autism Spectrum (and to those with other developmental disabilities)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This article reviews available research on toilet training for individuals on the autism spectrum (and other developmental disabilities). Programs commonly used when toilet training these populations, which are described in detail below, are often modeled after the methods of psychologists R. M. Fox and N. H. Azrin.

Prerequisites to Toilet-Training

Some researchers have indicated that there are prerequisites to initiate toilet training such as:

- regular urination and bowel movements (with infrequent dribbling)

- the ability to void urine in a large amount

- a demonstrated ability to sit on the toilet

Foxx and Azrin (1973) recommend that individuals should be able to walk, see, and grasp before toilet training begins.

Two Goals to Achieve Toileting Independence

In toilet training, two goals need to be met in order to reach independence: (1) continence, where the individual can recognize the sensation to go and (2) mastery of the chain of behaviors accompanying a visit to the toilet (e.g., walking to the bathroom, pulling pants down, eliminating in the toilet, wiping, pulling pants up, flushing toilet, washing and drying hands). These goals are the end of successful toilet training and are not prerequisites to begin toilet training.

Research on Toilet Training for Autism and Other Disabilities

Research dating back to 1963 indicates that utilizing guiding and prompting along with positive reinforcement (rewarding the individual for successful elimination) is the basic premise for a successful toilet training program for individuals on the autism spectrum and for those with other developmental disabilities. In 1971, Azrin and Foxx made a successful contribution to the literature when they developed one of the most comprehensive toilet training protocols, the rapid toilet training (RTT) method.

Despite the success of RTT and other research based programs, individuals often utilize pieces or parts of these programs when toilet training, rather than using the program as a whole.

This article reviews nine methods utilized in peer-reviewed toilet training studies, that have been presented in reputable journal databases such as ERIC, PsychInfo, and PubMed.

Many of these methods have been used in conjunction with one another in the studies reviewed, but not all methods have been utilized as a whole program in every study.

DISCLAIMER: THESE METHODS ARE NOT RECOMMENDATIONS BUT RATHER A REVIEW OF WHAT RESEARCH INDICATES AS EFFECTIVE TOILET TRAINING PRACTICES. PLEASE ASSESS YOUR SITUATION WITH YOUR CHILD/CLIENT AND CONSULT WITH MEDICAL PROVIDERS/THERAPISTS TO DETERMINE YOUR COURSE OF ACTION WHEN TOILET TRAINING.

9 Toilet-Training Methods

1 – Graduated Guidance

Graduated guidance is the most frequently incorporated behavioral component for toilet training individuals on the autism spectrum and those with other developmental disabilities. Gradual guidance involves prompting the individual through the steps of the toilet training process using the least intrusive prompts possible and increasing the level of prompting as needed.

For instance, if the individual needed prompting to pull down their pants, a least intrusive prompt may just include pausing and waiting. If that is not successful the trainer (parent, teacher, etc.) may try pointing to the pants. If more assistance is needed they may try telling the individual to pull their pants down, and if that is not enough they may use modeling (showing the individual what to do), guiding (guiding the person’s hand to pull down their pants) or hand over hand assistance to help the individual pull down their pants. This is an example of a least intrusive prompt to a more intrusive prompt. As the individual gains independence within a certain step, the prompts for that step can gradually be faded.

2 – Reinforcement-Based Training

Studies also indicate the benefits of incorporating positive reinforcement into a successful toilet training program. The most common type of reinforcement used is a preferred activity or food following a urination or bowel movement in the toilet.

However, research also indicates that gradually fading the reward can also lead to effective toilet training. For instance, initially the individual receives the reward every time they eliminate in the toilet, but once successful for a number of times, the reward is faded to every other time, every third time, until eventually only social praise (e.g., smiles, high-fives, verbal praise) is used as the reward.

More recently, negative reinforcement, in the form of response restriction, has entered toilet training protocols as a primary treatment component. In these studies, the participants were restricted from doing anything other than the behaviors necessary for toileting while in the vicinity of the toileting area. Similar to positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement strategies show to have a positive effect on toileting of individuals of varying ages and functioning levels. For more on response restriction see Toilet Training with Response Restriction.

3 – Scheduled Sittings

Scheduled sitting is also a commonly-used component in successful toilet training. In this procedure, the individual is placed on or in front of (depending on gender) the toilet at periodic intervals (e.g., every 15 to 30 minutes).

Once the individual eliminates in the toilet, they are given a reinforcer (e.g., preferred food or activity) and then they leave the toileting area.

Current research supports that once an individual is accident free with scheduled sittings (or standings), the time between sittings should be gradually increased (e.g., every 30 minutes to every 45 minutes) to increase the chances of self-initiation.

A timer or visual timer (for those who have trouble understanding a traditional countdown timer) can be used to indicate how long to sit on the toilet when attempting elimination (e.g., three minutes) and how long until the next scheduled sitting (e.g., 30 minutes).

4 – Elimination Schedules

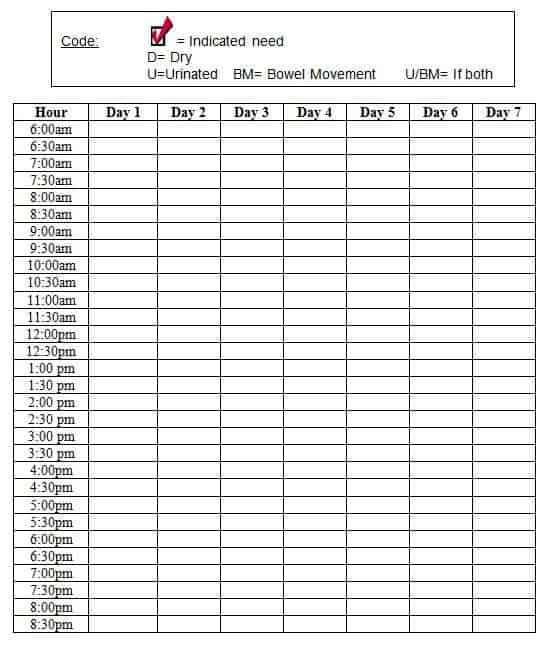

Elimination schedules are similar to scheduled sittings; however, rather than just having the individual go to the toilet at timed periodic intervals (e.g., every 15, 30, or 60 min.), the trainer first figures out a pattern of elimination by recording the time of day every time an individual urinates or has a bowel movement. Then the scheduled visits to the toilet are built around those times. This allows for more individualized training that capitalizes on the best times of day to intervene. To establish a pattern, check the individual for soiled or wet garments regularly and record the time and what type of elimination occurred. A chart such as the one below can be used to identify a toileting pattern.

Frequent checking and recording could be considered invasive for the individual, but is currently the best practice for obtaining reliable and valid data for voiding schedules. Check with parent/guardian and if possible the individual before considering this method. Keep in mind that if an individual is urinating in or soiling their pants, they would need to be checked anyway to ensure that they are clean and changing into dry clothes.

5 – Punishment Procedures

Modern research and practice indicates that positive behavior support (e.g., positive reinforcement, guidance) is more effective than punishment, and punishment procedures (e.g., spanking, time-out, taking away privileges) are not recommended during the toilet training process.

However, research does indicate that the use of over-correction through positive practice and restitution are effective procedures to incorporate in a toilet training program. With positive practice, the individual is directed to walk to the toilet from the site of the accident, pull down their pants and stand in front of or sit on the toilet, then pull their pants back up, go back to the accident site, and repeat up to five times (going back to the toilet, pulling pants down and up, and going back to the accident site). Restitution requires the individual to assist to the best of their ability with changing their wet/soiled clothes and cleaning the accident from the floor.

While these methods may be frustrating and challenging for some individuals, they have demonstrated positive results when used in conjunction with other positive methods (e.g., reinforcement, guidance, scheduled sittings).

It is important to note; however, that although over-correction procedures such as positive practice and restitution demonstrate high success rates in the studies in which they have been used, these methods are not referenced in literature very often. Most current literature discusses a positive reinforcement-based training method without the use of these procedures when working with individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities. Some studies, which demonstrate toilet training success, include positive approaches (e.g., guidance, positive-reinforcement, scheduled bathroom breaks) along with verbal feedback at the time of the accident (e.g., You wet your pants. We have to change), but do not incorporate positive practice or restitution. You can work with your child for a period of time to find what works best (e.g., only positive practices, positive practices with over-correction, positive practices with corrective feedback, etc.). You may find success with any of these methods.

6 – Hydration

Hydration procedures are often used in conjunction with schedules (i.e., timed sittings or elimination schedules). Hydration involves providing the individual with a large volume of preferred liquids. The trainer gives free access to the child’s/client’s favorite drinks because increasing hydration prior to scheduled sittings increases the chance of urination as well as positive reinforcement for urination.

Research suggests that hydration is an effective procedure when toilet training especially when used in conjunction with schedules; however it is important to be aware of potential risks. When too much water is ingested in proportion to an individual’s body weight, hyponaterma can occur (an imbalance of electrolytes in the body). It is important to drink water in moderation, but don’t overdo it. To read more about how to prevent hyponaterma see Hyponatremia Prevention.

Additionally, individuals with a history of seizures, hydrocephalus, spinal cord injury, and/or a current medication regimen with side effects of urinary retention (an inability to completely empty the bladder) should not be placed on a training program involving hydration.

Be sure to check with a medical provider before implementing hydration procedures.

7 – Manipulation of Stimulus Control

The above mentioned components of toileting interventions are highly effective in training individuals on the autism spectrum and those with other developmental disabilities; however, there are individuals within these populations who are resistant to training under these traditional approaches. In this case, manipulation of a stimulus control has shown to be effective. What does this mean? All of the basic components discussed so far are still incorporated into the training program; however, a condition in which the individual is likely to have an accident is removed during the time when elimination is expected to occur. For example, let’s say you record a pattern of elimination for a week, you have a sense of when the individual will urinate, and you know that the individual usually urinates in their pants or in the bath, etc. What you would do is remove these components from the toilet training situation and prompt the individual to the toilet when urination is expected to occur. So, if the individual is motivated or accustomed to urinating in their pants, you remove the pants for a period of time prior to prompting the individual to the toilet.

This approach may be considered intrusive and should only be done with parental/guardian (and/or participant) consent in a private setting and without any apparent discomfort to the participant. In settings which may be more open (school/residential facility) it may be effective to switch the material that the individual is used to (e.g. switching to silk from cotton) rather than removing the garments entirely.

8 – Nighttime Training for Diurnal Continence

In one study conducted by Saloviita (2000) – terminology to refer to individuals with intellectual disabilities is outdated in this study – a woman with an intellectual disability who had frequent night time bed wetting, significantly reduced her number of daytime accidents, after a nighttime toilet training program (known as the dry bed training procedure) was implemented. The program was intended to reduce nighttime bed-wetting and continued for 14 days. The program was discontinued after the individual had five accidents in one night; however, a follow up of the individual showed that day-time accidents immediately began to decrease after implementation of the dry bed training procedure and were virtually diminished after one year. It is important to note that this was not a controlled study and therefore, true treatment effects need to be interpreted with caution.

The dry bed training procedure includes the following:

a first night of intensive training which includes positive practice (discussed above) one hour before bedtime, a drink at bed time, an alarm that sounds when the individual wets the bed, hourly waking (waking the individual to use the toilet every hour), and cleanliness training (teaching the individual to clean the bed/change clothes after an accident occurred).

post training supervision which includes an alarm, positive practice if the individual wet the bed the night before, waking the individual to use the bathroom before the caretaker goes to bed, cleanliness training if the individual wets the bed, and praise if they are dry in the morning.

If the individual is dry for 7 straight days, the alarm is removed and if the bed was wet in the morning cleanliness training would be given and positive practice would be used before bed that evening. If the individual is wet twice in a week, post training supervision is started again.

9 – Priming and Video Modeling

Priming is the act of preparing the individual for a subject or activity before it actually occurs. An example would be showing a video about toilet training to a person before attempting to toilet train them. The purpose is to increase the likelihood that the behavior will be completed successfully by familiarizing the person with the concept and expectations. Data indicates that toilet training videos can increase the speed at which individuals on the autism spectrum can acquire toileting skills. While further studies are warranted to determine if priming is a necessary component to of a successful toilet training program for individuals on the autism spectrum, preliminary data are supporting the use of videos in teaching toileting.

However, a popular app called See Me Go Potty allows you to choose your gender and watch the steps of toileting. You can even create and name your character.

References:

A Parent Training Model for Toilet Training Children with Autism

Toilet Training Children With Autism and Developmental Delays: An Effective Program for School Settings

Guidelines for Potty Training Program by Foxx and Azrin

Toilet Training Individuals with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities: A Critical Review

Recommended Articles:

15 Behavior Strategies for Children on the Autism Spectrum

What is an Intellectual Disability? (with Printable Milestone Checklist)

Potty Books and Tools for Kids

Rachel Wise is the author and founder of Education and Behavior. Rachel created Education and Behavior in 2014 for adults to have an easy way to access research-based information to support children in the areas of learning, behavior, and social-emotional development. As a survivor of abuse, neglect, and bullying, Rachel slipped through the cracks of her school and community. Education and Behavior hopes to play a role in preventing that from happening to other children. Rachel is also the author of Building Confidence and Improving Behavior in Children: A Guide for Parents and Teachers.

"Children do best when there is consistency within and across settings (i.e., home, school, community). Education and Behavior allows us to maintain that consistency."